9

I would like to keep working on it. At this point I have only

been working on it for about a year and a half. There is a

lot of post-capture work done on the images themselves.

During post-processing I edit for shadows, highlights,

exposure and some of the other details. For instance, in

the churches, sometimes I shot from the floor - when you

tilt the camera up, vertical lines that were parallel shift

inwards towards the top, also known as keystoning. With

any built environment, you see that. So I had to correct for

these lines and make them parallel, and sometimes I also

had to tile several shots to combine them.

In creating these works I had to consider the format. Some

images were tightly cropped to the confessional while

others showed more of the surrounding space. I then

became interested, in how the object communicates with

the fragments of the space. I love the little things – the fire

extinguishers, the speakers, the signage, etc. I hope that

the series evokes a sense of curiosity, and I also hope that

people take note of the kind of modern elements that are

surprising; the church is historic and rich with interiors

dating back hundreds of years, these however also house

objects that suggest very contemporary pragmatic issues.

What exactly was the moment or idea that made you

want to work on this project?

When I was young, my family agreed to raise their children

Catholic, so I went to church and did my First Communion

when I was eight years old. Because I was so young I

didn’t have any material to confess, so I fabricated some

things. Ironically, the first lie I remember telling was in the

confessional to a priest.

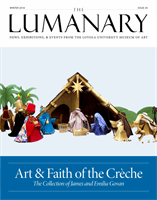

When I went to Italy in 2014, I was reminded of that strange

event. It drew me in. The confessional is an object that’s

often overlooked. One day I came upon a church up on

a hill - it’s the picture on the last cover of

The Lumanary

(refer to top right image). It was so strange, I walked in

and not a single person was there. It was a very old church.

I had a direct shot of the confessional, and the light was

beautiful. Because I didn’t have anything to set my camera

on, I placed it on the ground and I put my lens cap under

my lens so it just tilted it a little bit. In order to compose

and focus the scene through the viewfinder, I had to lay

down on the stone floor of the church. There was no one

around me, just this beautiful object in front of me, and I

took the shot. That was when I felt I really wanted to pursue

this project no matter what.

What is (for you) specifically appealing about the

object of the confessional itself?

The object is a contested site - not everyone agrees about

what happens inside. There’s a faith-based interpretation of

forgiveness or atonement, and then there are other types of

interpretations, some of them perhaps even negative. But

at its heart, it is a metaphor for self-perception and taking

responsibility, for communication and understanding your

place in what has happened in your life. Confessing allows

you the opportunity to let go of that through your own

reflection, acknowledgement, and intention to change or

grow. Through these acts and discussions, you can then

rejoin a community. Some view it in a negative way, such

as, “Well most people won’t try to be a better person, it just

gives them a chance to continue on as they have without

consequences.” But I don’t view it in that way, I see it as

a motivation to improve. There’s something very human

and powerful about that - the hope that we can “get better”

even as a culture, nation, or a global community.

Images:

Basilica di Santa Sabina all’Aventino, Rome,

2014, Marcella Hackbardt.

Collection of the artist;

Basilica di San Marco, Milan,

2015, Marcella Hackbardt.

Collection of the artist.