Although it was mid-September, Graffius had prepared

me to dress warmly because of dampness and drafts.

We spent the day moving through the long halls and

common rooms dodging neatly dressed, muffler-

wearing students going to class. I realized in the chilly

atmosphere that housing a collection in a building as

old as Stonyhurst—part of its dates to the late 16th

century—presents challenges of conservation and

storage that we at LUMA cannot begin to imagine.

Graffius kindly pulled objects out of collection

storage for me to look at while talking me through a

chronicle of the medieval and Renaissance Church.

Each new object she showed me had one more story

testifying to the history of the Society of Jesus and the

oftentimes thorny history of the Jesuits in England.

It is important to put the objects in the D’Arcy

Collection that had come from Stonyhurst into

context. Provenance is the “holy trail” of ownership

in the history of a work of art. It is through

provenance that we can validate authenticity and

are provided clues to the interconnected weave of

ownership from maker to buyer from the past to

the present day. Beginning in the late 1960s and

throughout the 1970s, founding director Fr. Donald

Rowe, S.J. began building the D’Arcy. His hope was

to assemble a collection that would provide Loyola

students with a contemplative respite from their

studies. Objects in the D’Arcy with ties to Stonyhurst

include the Collector’s Chest by Wenzel Jamnitzer

(1570)

and the four late 16th-century carved wood

Evangelists. How did these pieces come from Hurst

Glen to Chicago? Like many private English schools

in the ’60s and ’70s, Stonyhurst was in need of funds

and willing to part with objects whose provenance

was not integrally related to the history of the school

or the house itself. A satisfactory measure would be

to sell the materials to another branch of the Society.

And so these beautiful objects came to Loyola and

are now part of LUMA.

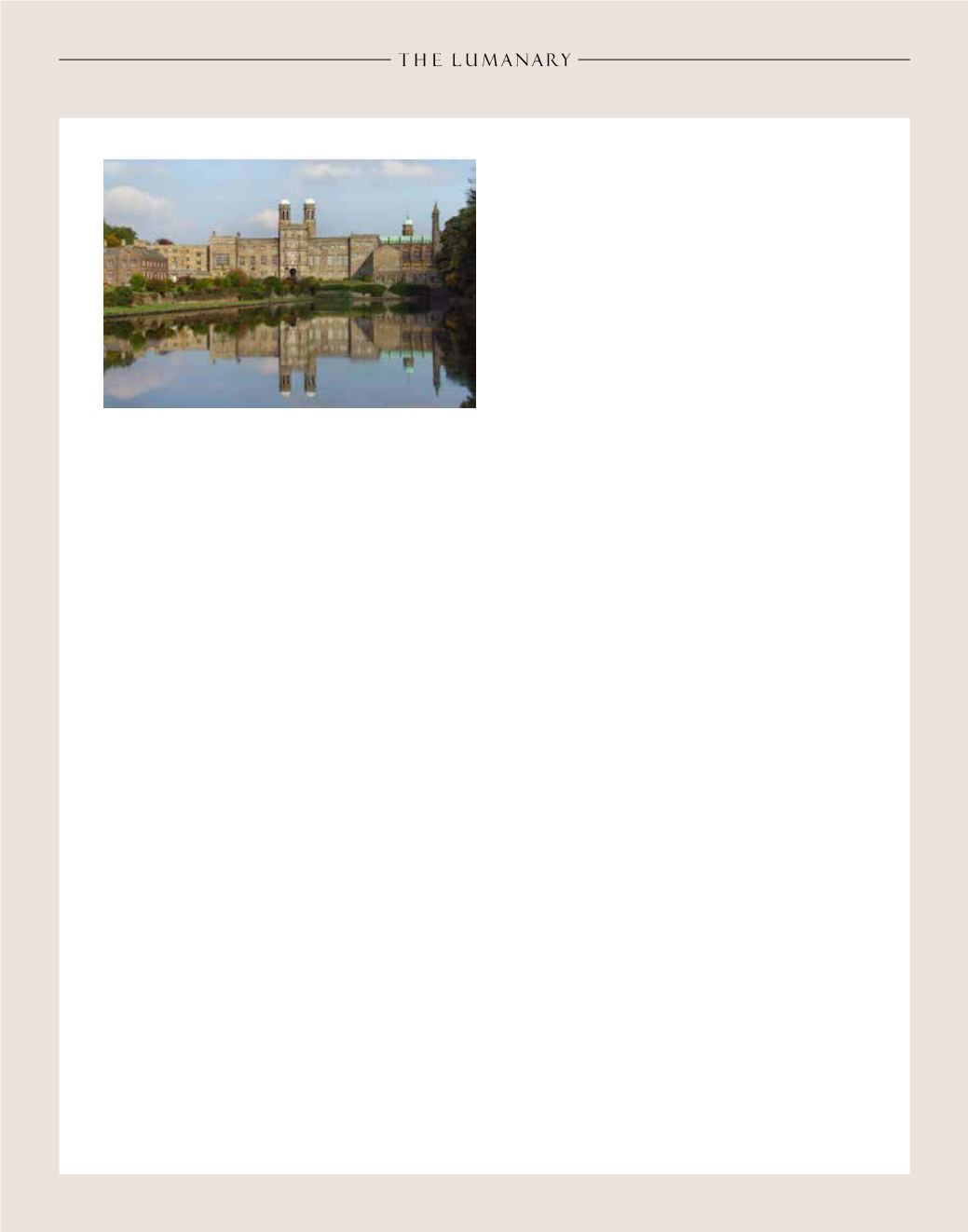

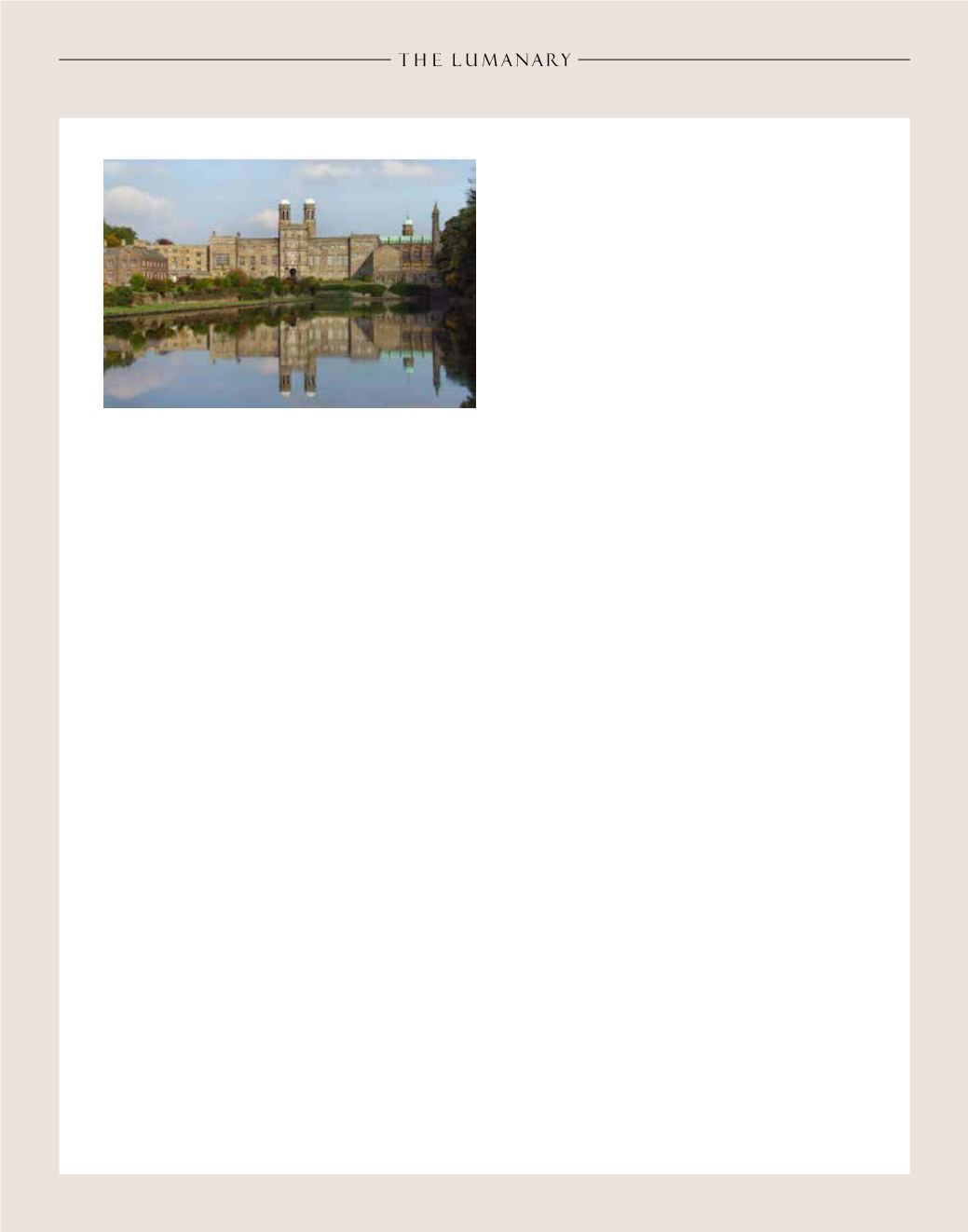

Stonyhurst was founded in 1593 by English Jesuit

exiles in the Channel port of St. Omer in the Spanish

Netherlands. Anti-Jesuit sentiment caused the school

to move several times in the mid-18th century—first

to Bruges in 1762 and then to Liège in 1774. The

Jesuits fled the advance of a French revolutionary

army for this reclusive corner of England in 1794,

becoming tenants of an alumnus, Thomas Weld. The

scion of a steadfastly Catholic, old Lancashire family,

the Shireburns, in whose ancient 17th-century pile he

settled his former teachers.

A modern curriculum, designed to strengthen the

Church and reassert Catholic orthodoxy during the

confusing and seriously difficult times in Europe,

was a distinguishing element in the new order of the

Society of Jesus, established by Ignatius of Loyola

in 1540. According to Maurice Whitehead—an

historian at Swansea University and editor of

Held in

Trust: 2008 Years of Sacred Culture; A Catalogue of

an Exhibition from the Stonyhurst College Collections

(2008)—

by the 1700s, there were 760 Jesuit schools

established to educate young men throughout the

world. The school at St. Omer was started specifically

for English Catholics; Catholic institutions were

banned under the Protestant Elizabeth I. Jesuit priests

slipped back into England to minister to the faithful,

known to the Protestant authorities as recusants (as in

1