9

How did you get into this project? What drew you

into it in the first place?

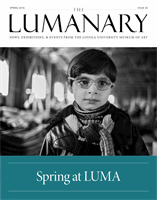

What really drew me to it was years and years of being

exposed to the narratives of people who were forcibly

displaced in various parts of the world. What I began to

see in the images was there were stories in people’s gazes.

A lot of my work was portraiture at the time. It began to

frame the way I was seeing these people. Refugees live in

fear of war, of reprisal, of their future, and of a vast and

uncertain present. They are not only victims, but also

people trying to find a home in a way that is valiant and

heroic. They have a sense of humor, take great care of

their dignity, communicate with others and with me in

a way that was profoundly human, and of course they

are survivors.

Were there commonalities of the narratives of the

refugees that you spoke to?

Yes, there were many commonalities. One is what I call

the geography of fear. Refugees are moving across the

border, which represents a very scary place. The second

is the notion of dislocation. Refugees are people who

have suffered great loss. The third is the quest of home.

Everyone who is a refugee is attempting to recreate a

sense of home.

In your work, how have you approached political and

contested subject matter such as this?

I am really interested in documenting invisibility, the way

that refugees are not seen, rather than a critical moment.

At the end of the day they are not refugees, but actual

people. There is something about that invisibility that

is very hard to get at in this present political discourse.

We are looking at least sixty-five million people who are

displaced worldwide for one reason or another. Before

they are dislocated, they are diverse in terms character

as any one of us in the city of Chicago, or the United

States for that matter.

Have you seen perceptions of people being displaced

change over time?

I think that there are larger discourses around refuge,

flight, and migration that have dominated and challenged

different societies. If we look at the mass migration of

asylum-seekers, especially in 2014, 2015 and 2016, there

was an initial societal acceptance. What took place in

Europe was that state institutions had a difficult time

dealing with the large numbers of new arrivals. We

saw an unprecedented movement of people assisting

refugees, but we also saw another group of people who

thought that the state institutions were crumbling and

that refugees were presenting a threat. In the US we see

a similar similarities. There are caring people trying to

welcome refugees into their homes. At the same time,

there is a lot of fear. Inmany ways, perhaps this exhibition

is trying to demystify perceptions of refugees. These are

human beings. These are people that have gone through

a great deal. Let’s begin to pierce that veil, so to speak, in

order to understand how refugees have been rendered

invisible by political discourse, by social discourse, and

by history. Then begin to step back and say, “Who are

you?” Let’s begin to have a dialogue. I hope this exhibition

will show the humanity, souls, and circumstances of

these refugees.

What do you think your responsibility is as an artist

with this kind of subject matter?

It’s to do my very best to relay what I’ve seen and felt, both

as ideas, but also as images that convey an experience.

How did you decide on the exhibition title, “They

Arrived Last Night?”

I spent a great deal of time speaking with people who

literally had arrived last night. Sudanese who crossed

the border into South Sudan. An Ethiopian woman in

Calais who arrived and wanted to make the crossing

into England. Syrians who crossed into Jordan. The list

is extensive. There was always an openness about them,

especially in that moment of arrival. That moment of

feeling safe from an immediate past, but also extremely

unsure of the future, was a concept I felt obligated

to explore.